Nike sues over shoes linking the company to Satan.

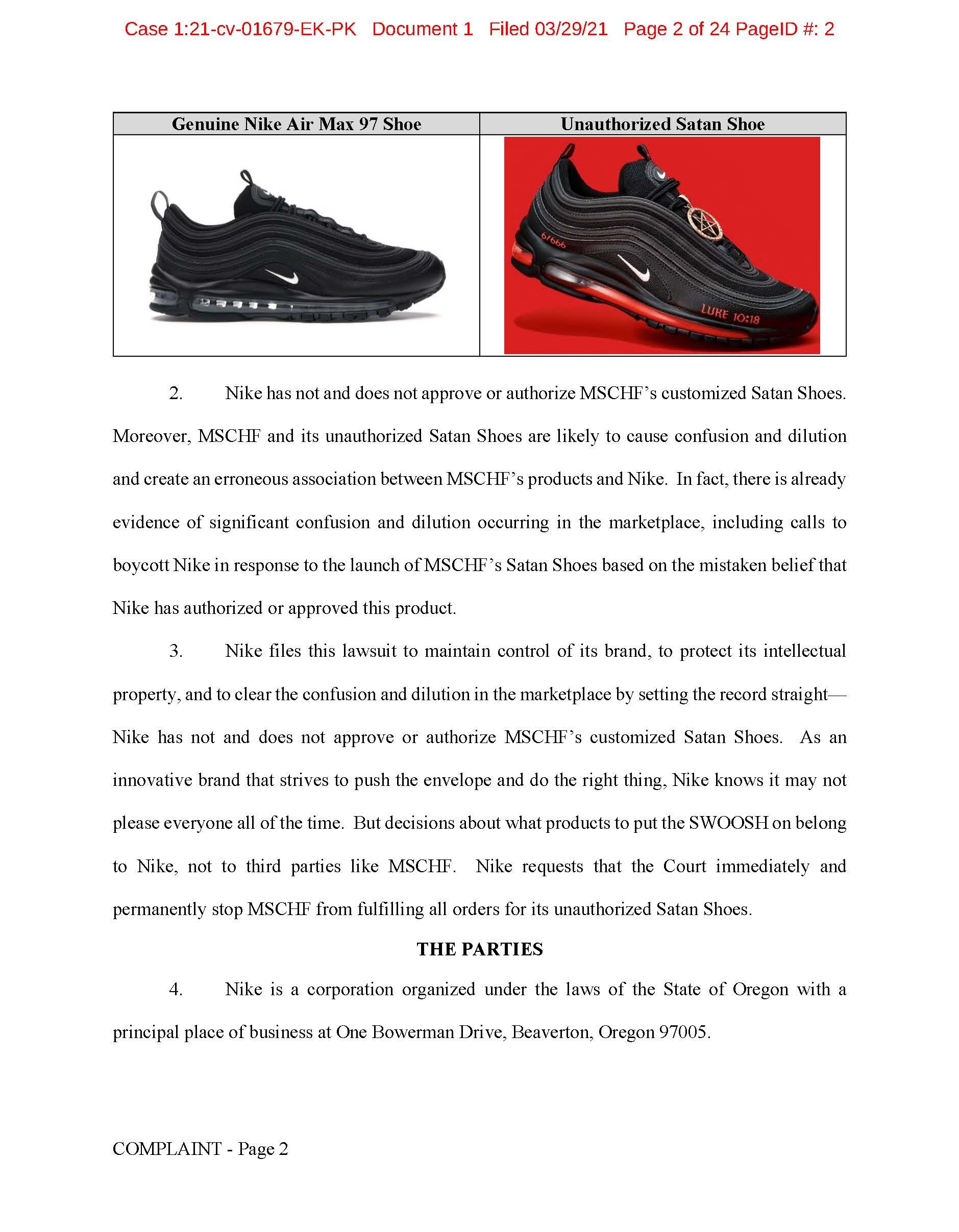

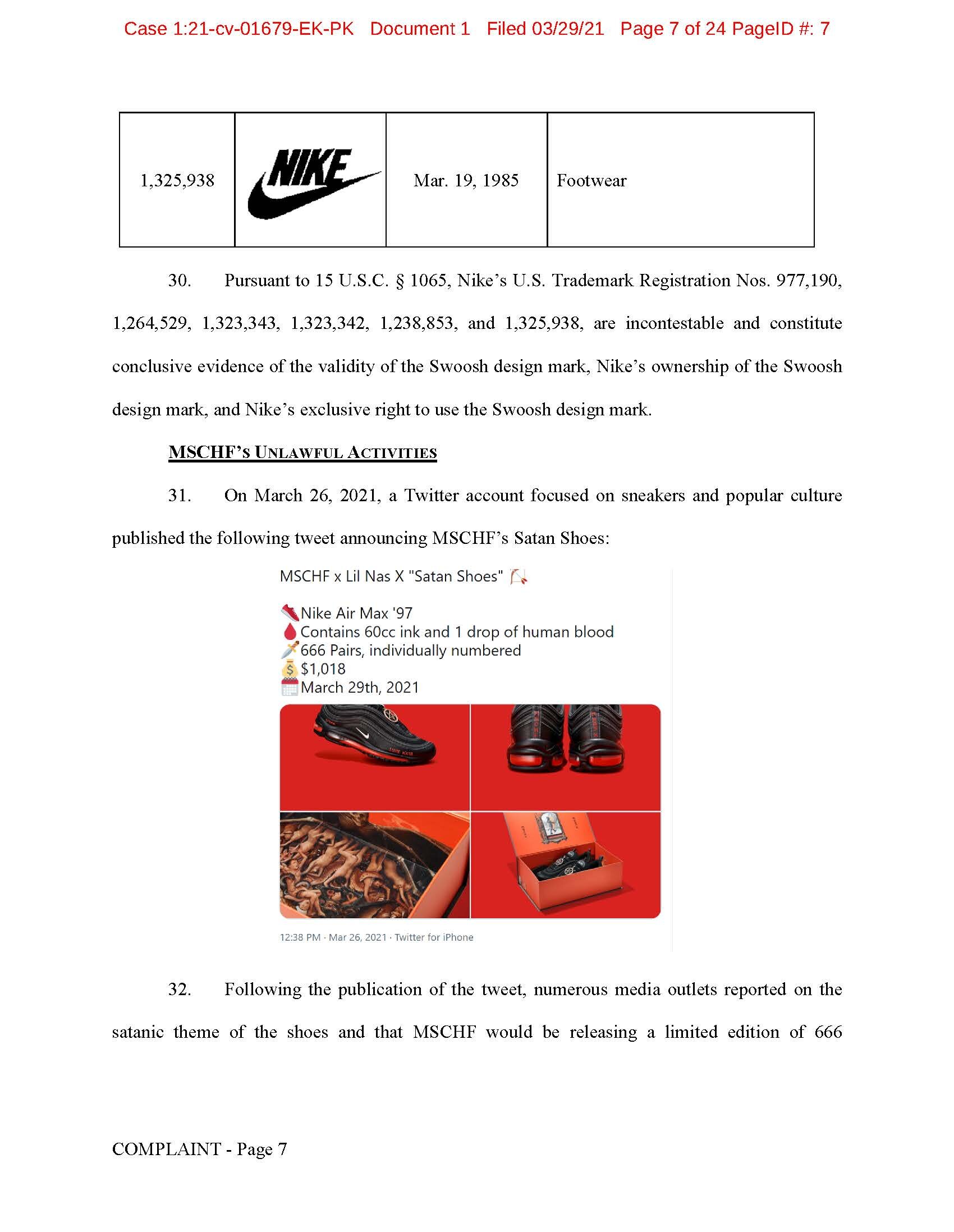

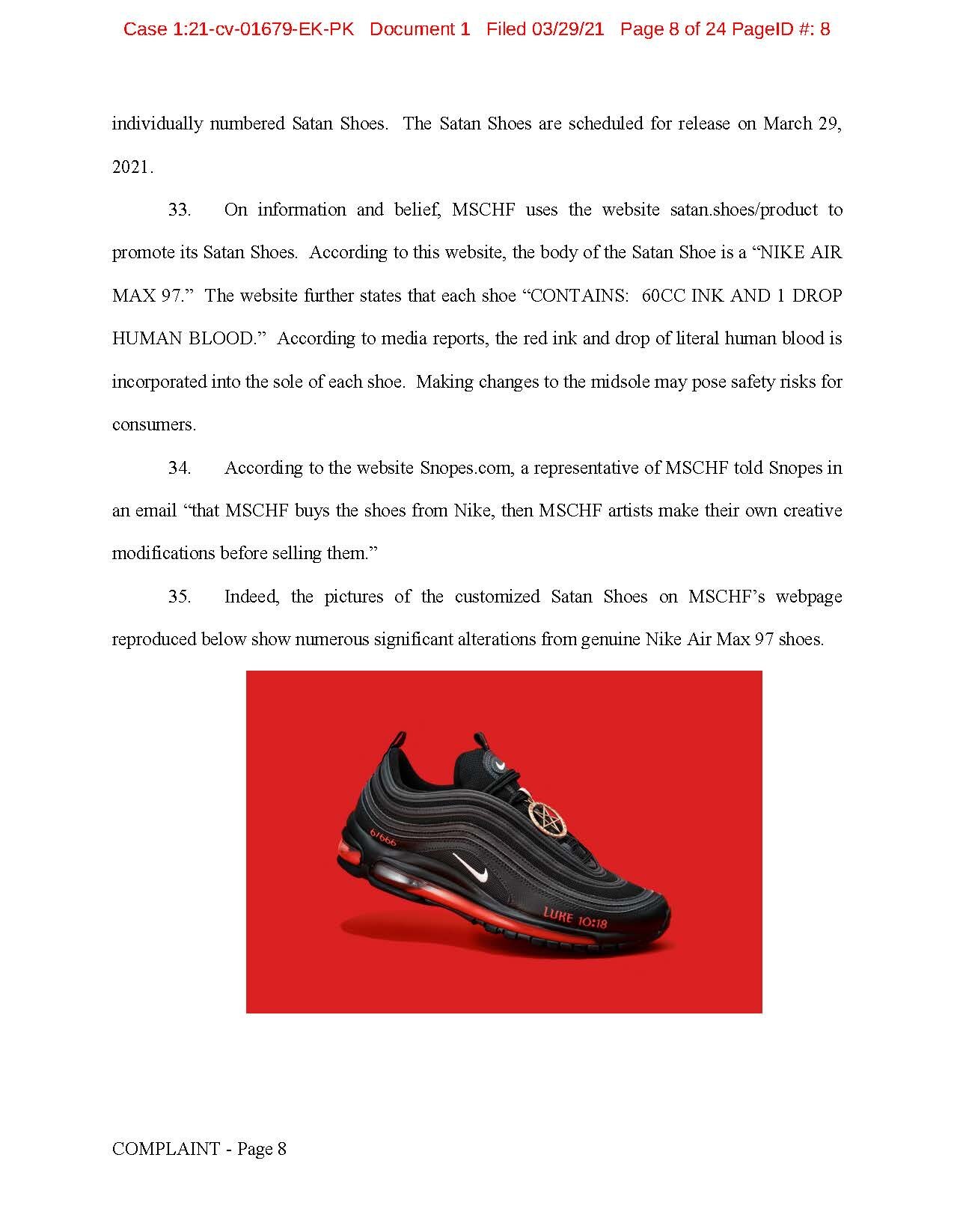

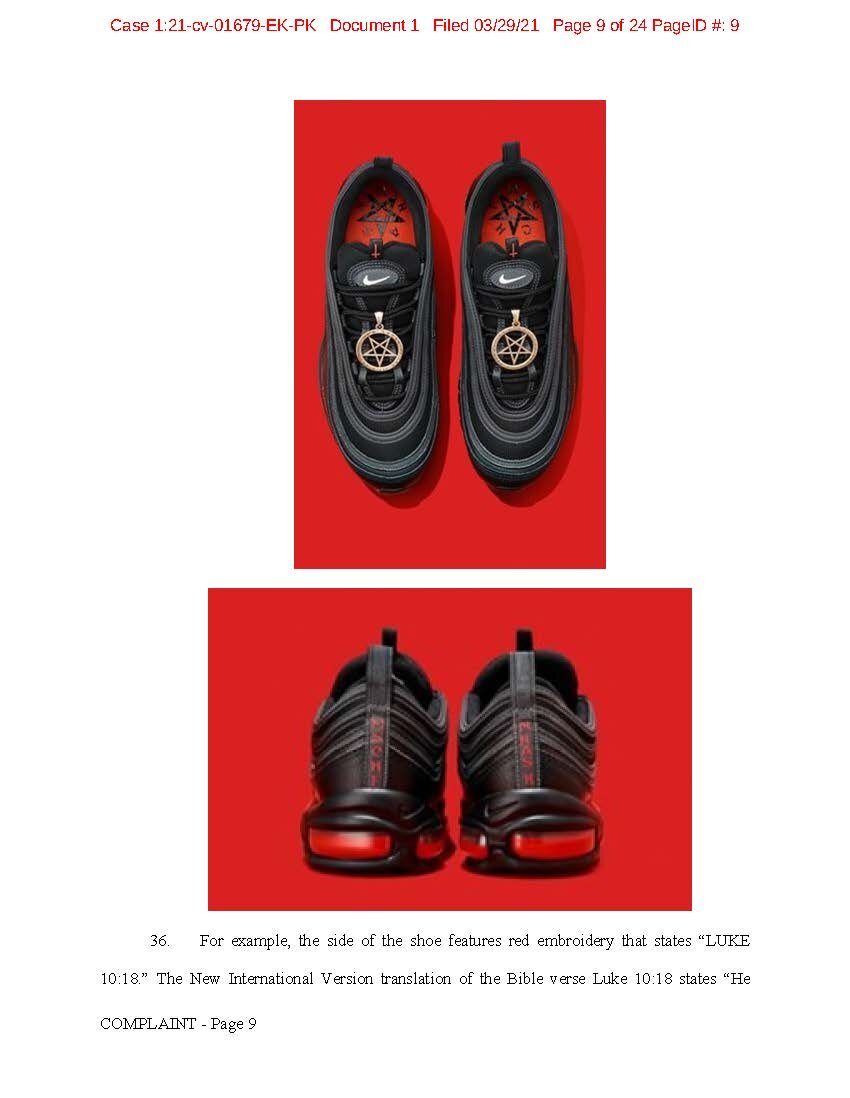

An art collective called MSCHF altered Nike’s Air Max 97 shoe by adorning it with a bronze pentagram charm, etching a bible verse on its side about Satan’s fall from Heaven, and depicting a red inverted cross on the tongue. Oh, and also by injecting a drop of blood inside the mid-sole drawn from team members of MSCHF. The collective named the modified version of the sneaker “Satan Shoes” in collaboration with Lil Nas X and the release of his music video for “Montero (Call Me By Your Name).” All 666 of the shoes sold out on Monday priced at more than $1,000 a pair.

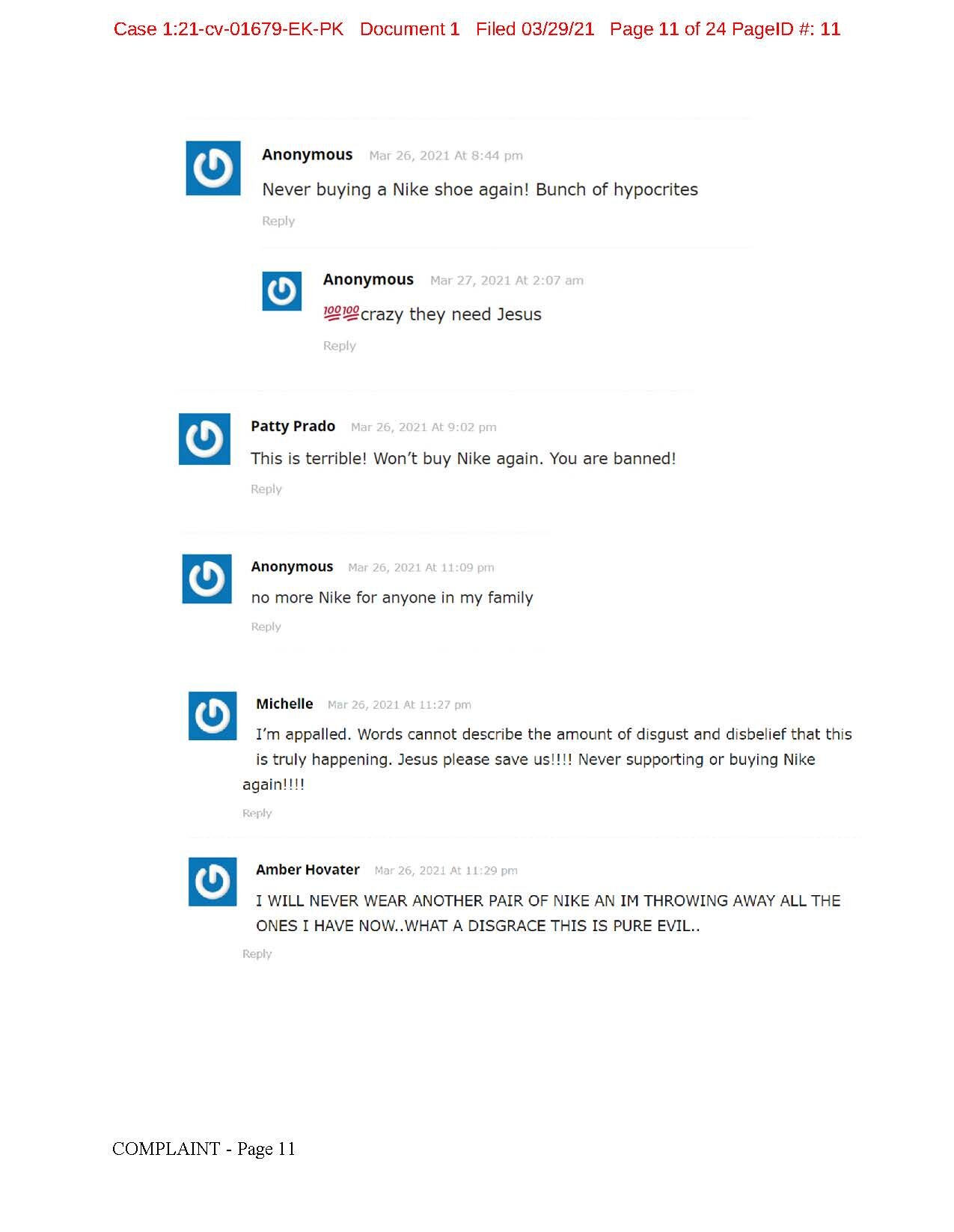

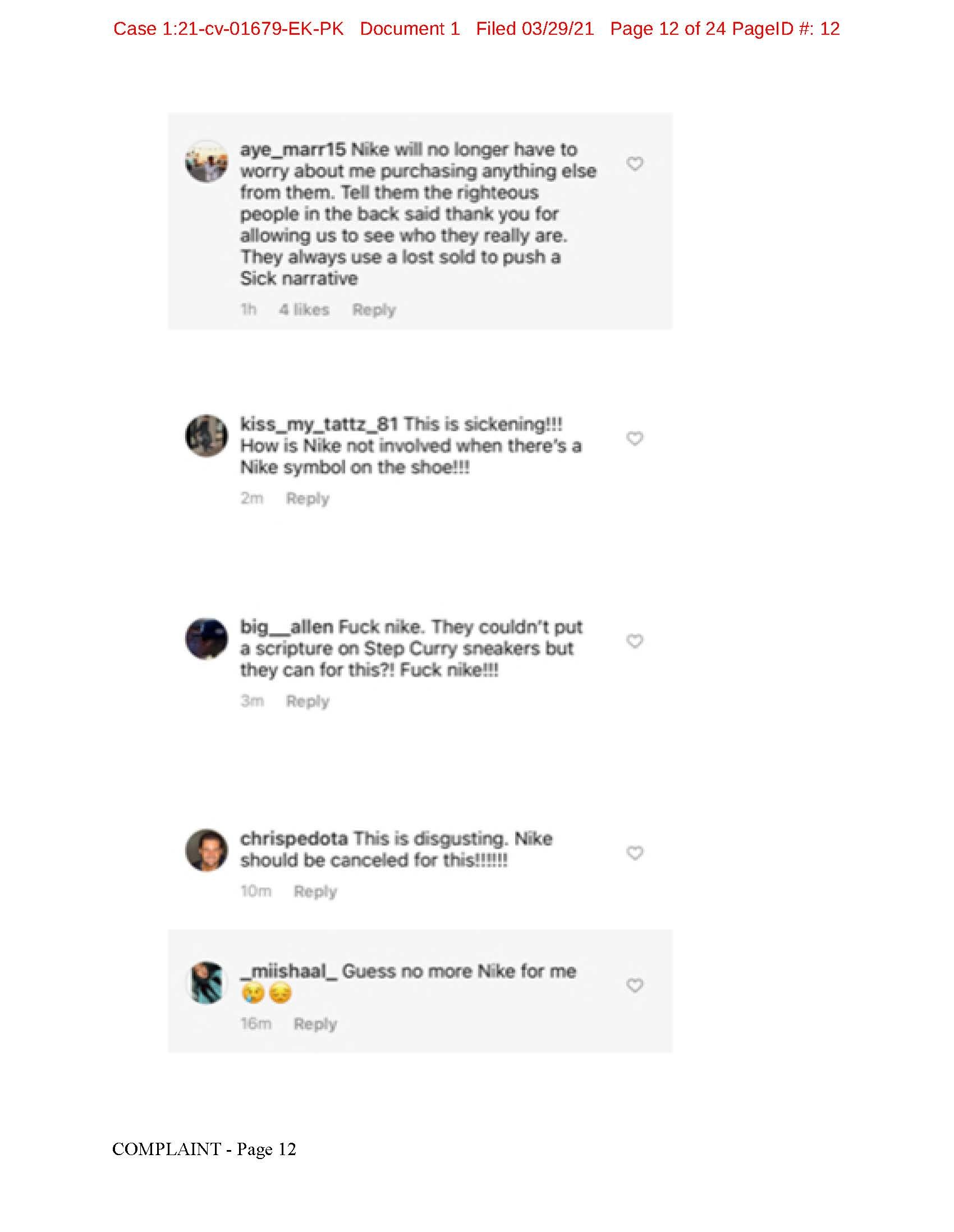

Then came the backlash from the pajama people. Social media erupted over Nike’s apparent endorsement of such an evil endeavor, as users threatened to boycott Nike over its connection to the controversial shoes. For example, a user named Michelle wrote: “I’m appalled. Words cannot describe the amount of disgust and disbelief that that this is truly happening. Jesus please save us!!!! Never supporting or buying Nike again!!!!” Nike was quick to claim neither an association with the modified shoe nor a relationship with Satan (smart), offering an official statement to several news outlets in response.

Then Nike politely asked MSCHF to stop fulfilling orders for the unauthorized shoes, and by politely, I mean Nike filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York, alleging trademark infringement in violation of 15 U.S.C. § 1114, false designation of origin/unfair competition in violation of 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a), trademark dilution in violation of 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c), and common law trademark infringement.

This post will focus on the dilution claims. Under 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(2)(B), dilution by blurring occurs when “an association arising from the similarity between a mark or trade name and a famous mark that impairs the distinctiveness of the famous mark.” In its lawsuit, Nike claims MSCHF’s wrongful use of Nike marks will likely blur and whittle away the distinctiveness and fame of the Nike Asserted Marks.

Meanwhile, under 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(2)(C), dilution by tarnishment occurs when a famous mark, like the Nike swoosh, is linked to products of shoddy quality, or is portrayed in an unwholesome or unsavory context, thus harming the reputation of the famous mark. For example, Anheuser-Busch successfully enjoined a company from selling a shirt that transformed the Budweiser logo to Buttwiser, as the modified logo portrayed Budweiser in an unflattering and/or unsavory manner. Anheuser-Busch Inc. v. Andy’s Sportswear Inc., 40 U.S.P.Q.2d 1542 (N.D. Cal. 1996). In its lawsuit, Nike alleges that associating the Nike Asserted Marks with satanic imagery is likely to cause dilution by tarnishment.

The complaint pits infringement and dilution against the First Sale Doctrine, a legal theory that gives individuals who buy a copyrighted item the right to resell the product without the creator’s explicit permission. The doctrine enables art collectives like MSCHF to exercise an established brand of creativity to customize purchased shoes and resell them for thousands of dollars. Nike has done little to stop artists in the past because the modified versions undoubtedly contribute to the sneaker culture upon which Nike relies for cultural prominence. For example, MSCHF previously released a modified version of the Nike Air Max 97 that customized the shoe by adding holy water taken from the Jordan River to the mid-soles. The collective named the sneaker “Jesus Shoe,” and Nike did not initiate a lawsuit in response and did not disassociate with Jesus (also smart).

While Nike certainly has a case to make against MSCHF due to the potential for the company to unfairly suffer harm to its brand from the art collective’s continued fulfillment of the orders, resolution of the case could also have an unintended consequence on a part of the creative art industry existentially reliant on the First Sale Doctrine.